If you’re dressing on a budget, one of the most popular pieces of advice out there is to buy off-the-rack suits in the best fit you can get, and then take them to a tailor for custom adjustments.

That’s good advice. You’ll find it in several articles right here on the Art of Manliness.

But if you’re really going to get any benefit out of having your suits adjusted, you need to know a little bit about tailors and the kinds of adjustments they can (and can’t) make.

You also need to know what a “good” fit actually looks like.

Tailors vary in skill and in how they communicate the work they’re doing, so getting a suit adjusted is only going to deliver a good return if you can make your exact needs clear.

Below, we give you an easy-to-follow rundown on how your suit should fit.

What a “Good Fit” Looks Like

When you try on a suit, you’re looking for a good fit in what’s called your “natural stance.”

That means standing up straight, preferably in the kind of dress shoes you’ll be wearing with your suits, with your arms relaxed at your side.

It’s not actually a very natural posture for a lot of us, but it is the base from which most of our movement flows. If the suit doesn’t fit well in this stance, it’s not going to move comfortably with your body either.

Practice standing in that relaxed, upright pose, and then start trying on suits in that posture. Look for a good fit in the following areas when you’re in your natural stance:

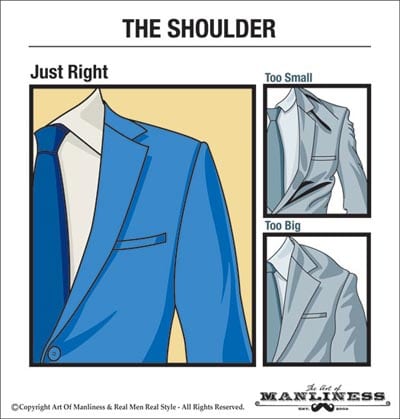

The Shoulder

A well-fitted shoulder lies flat. The seam on top of the shoulder should be the same length as the bone under it, and should meet the sleeve of the suit right where your arm meets your shoulder.

If the seam that connects the sleeve to the jacket is hiked up along your shoulder bone, or dangling down on your upper bicep, the jacket is never going to sit properly. In these instances, you’ll see “ripple effects” that create lumps or wrinkles on the sleeve and the top of the jacket.

Shoulders are one of the hardest parts of a jacket to adjust after construction, so don’t buy a piece with an ill-fitted shoulder. Odds are you’ll never be able to get it quite right with post-purchase alterations.

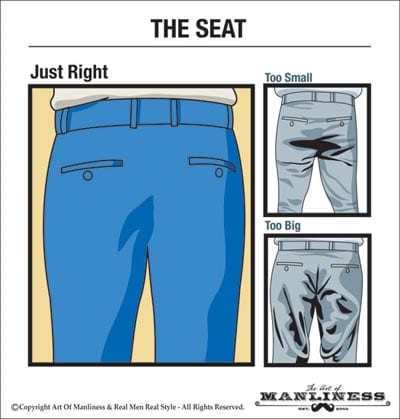

The Seat

The back of your trousers should be a smooth drape over the shape of your rear end — whatever that happens to be.

A good fit in the seat will lie loosely against your underwear, without pulling tight against your butt or draping loosely down your thighs.

You can spot a bad fit in the seat when there are horizontal wrinkles just under the buttocks (caused by too tight of a fit), or by loose, U-shaped sags on the backs of the thighs (caused by too loose of a fit).

A tailor can “take in” a seat to make it tighter in the back without too much difficulty, but there’s a limit to how far he can go. If the seat was way too loose to begin with, it’s not possible to adjust it to fit without pulling the pockets out of place.

Unless the pants have an unusual amount of spare cloth on the inside, seats can’t be “let out” very far to make the fit looser. Err on the side of too loose rather than too tight when buying.

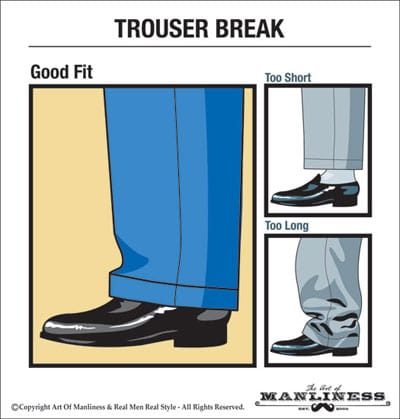

Trouser Break

The “break” is the small wrinkle caused when the top of your shoe stops your trouser cuff from falling to its full length.

This should be a small, subtle feature. One horizontal dimple or crease is usually ideal. The cuff should indeed rest on the top of your shoe — there needs to be contact — but it shouldn’t do much more than that. The trouser can fall a touch longer in the back than in front, so long as it’s still above the heel of the shoe (the actual heel, not just the back of the shoe).

This is one of the easiest adjustments to make, so you can rely on making some changes here if you need to. In fact, dress pants are often sold unhemmed, with the assumption that the purchaser will take the trousers to a tailor (or make use of the store’s tailor if there is one) to have the cuffs fitted.

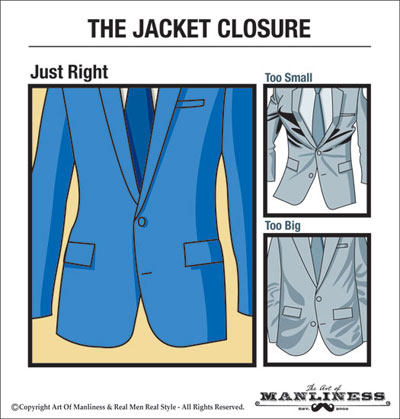

The Jacket Closure

When you are wearing a suit and standing, you should have the jacket buttoned (you know the jacket buttoning rules, right? Click here to learn!).

This means that part of the trying-on process is checking how the front of the jacket closes over your body.

Close a single-breasted jacket with only one button when you’re testing the fit, even if it’s a three-button jacket. You’re looking to see if the two sides meet neatly without the lapels hanging forward off your body (too loose) or the lower edges of the jacket flaring out like a skirt (too tight).

The button should close without strain, and there should be no wrinkles radiating out from the closure. A little bit of an opening at the bottom of the suit is fine, but the two halves beneath the button shouldn’t pull apart so far that you can see a large triangle of shirt above your trousers. (Ideally, you shouldn’t see any, though a bit is socially acceptable, especially when you move.)

Taking in or letting out the waist to help the jacket close more comfortably is not a difficult adjustment, but it’s one with limits. Don’t expect a tailor to be able to make huge changes here. If the jacket closure looks really bad unaltered, it’s probably due to problems beyond the waist measurement, and you should be looking for a different jacket rather than planning on getting that one altered.

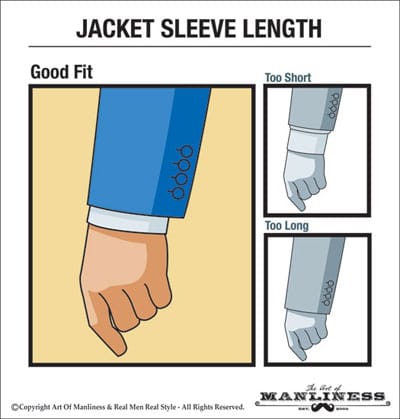

Jacket Sleeve Length

“A half-inch of linen” is a good, old-fashioned guideline for the relationship between a suit jacket and the shirt worn under it — about half an inch of the shirt cuff should be visible beyond the jacket cuff.

That said, it’s a general guideline, and you don’t need to get too obsessive. What you do need to be sure of is that the suit sleeve doesn’t rise above the cuff entirely — the seam where the shirt cuff joins the shirt sleeve should never be visible.

Similarly, the jacket sleeve should never hide the shirt sleeve entirely. At least a small band of shirt cuff should always be visible.

For most men, that ends up being a jacket sleeve that terminates just above the large bone in the wrist. But everyone’s arms are slightly different, and sleeve length is a very easy adjustment for a tailor to make, so get the best sleeve length you can (erring on the side of too long if possible) and then have it adjusted to fit.

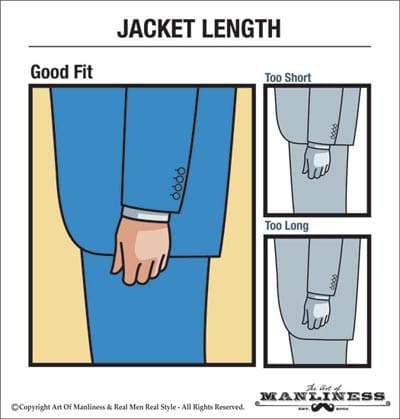

Jacket Length

Not enough time or writing gets devoted to the overall length of men’s jackets. It’s more important than most people think!

A good suit or sports jacket should fall past the waist and drape over the top of the curve formed by the buttocks. An ideal fit will cover a man down to the point where his butt starts to curve back inward, and stop there (but anywhere in that general region is okay).

The hands are also a good marker here, and this is why it’s important to have your arms relaxed in your natural stance. The hem of the jacket should hit right around the middle of your hand — at or just past where the fingers meet the palm.

If the hem of the jacket is sitting on top of the butt, with a small little flare in the back, it’s too short. If it falls past the bottom entirely, longer than the arms, it’s too long. The hem can be adjusted upward without too much trouble, but if you go too far the front pockets start to look out of proportion, so don’t count on more than an inch or two of adjustment here.

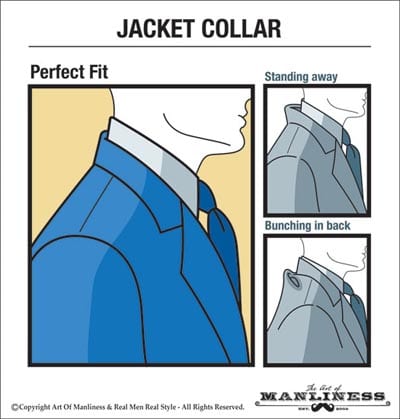

Jacket Collar

It’s easy to tell a well-fitted collar from a poorly-fitted one, although identifying the cause of the bad fit can be challenging.

Your jacket collar should rest against your shirt collar, which in turn should rest against the back of your neck. All of these should touch lightly, without significant gaps in between.

If the collar is too loose, it’s very easy to spot — there will be a gap where it’s flopping back off your neck.

A tight collar is a little harder to spot on a jacket, since (unlike a shirt collar) it’s almost all in the back. Turn from side to side as needed and check it out in a mirror. A tight collar will create bunching and folds just beneath it, and often wrinkles the shirt collar underneath it as well.

Bad collar fit could just mean the neck size is wrong for you, but it’s often caused by a larger fit issue: bad shoulder sizing, a back panel that’s too small for you, or even a jacket that’s constructed with more of a forward or backward tilt than your neutral stance.

Since these adjustments cost time and money to fix, you want to get as good of a fit in the original jacket as possible at the collar.

Four Automatic “Bad Fit” Warnings

There are a couple of easy to spot problems that are major warning signs. A suit with these “bad fit” signs is one that you probably won’t ever be able to adjust to a really good fit.

Unfortunately, most of them are caused by the core structure of the suit — and that means that your body just isn’t a good match for the way that particular brand makes its pieces.

Be patient, try on lots of brands, and don’t compromise (unless you know it can be fixed!).

If you can’t afford bespoke (made to order), an adjusted off-the-rack suit can work — but you have to start with a pretty good fit in the first place, or it’s never going to get the results you want.

Unless you want to pay for alterations, be careful buying any jacket that’s showing these serious warning signs:

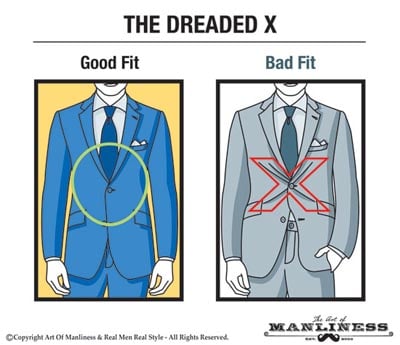

The Dreaded X-Shaped Button Strain

If you can see wrinkled lines radiating outward from your jacket button when you close the jacket, it’s too tight and will need adjustment.

The Dreaded X, as my friend Barron over at Effortless Gent likes to call it — is not a look you seek in a well-fitted jacket.

Front button strain is indicative of a bad fit in the torso, and it can go beyond just the waist size — you’re probably straining at the shoulders or in the back, too. On a more basic note, it also means the button is going to be prone to popping off.

Don’t buy a jacket that shows strain lines radiating outward from the button. If you’ve got an old jacket that used to fit but has started showing them, it’s possible that you’ve either gained weight or accidentally shrunk the jacket in a wash — in that case (assuming the fit was good before), you may be able to have the waist let out a little and keep the jacket in use.

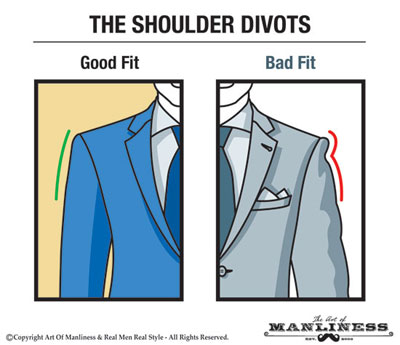

Shoulder Divots & Upper Arm Wrinkles

If the sleeve of the jacket seems to dip in slightly just under the shoulder, and then flare back out again, the shoulders are too big. What you’re seeing is the shoulder padding protruding beyond your arm, and the cloth of the sleeve tucking back in underneath it.

You can also get those wrinkles if you’ve got a somewhat slouched stance and the jacket is stiffly-constructed for a more upright posture. In either case you’ll need to get a smaller size, so that the seam where the shoulder meets the sleeve matches up with your body’s shoulder, or give up and try a different brand.

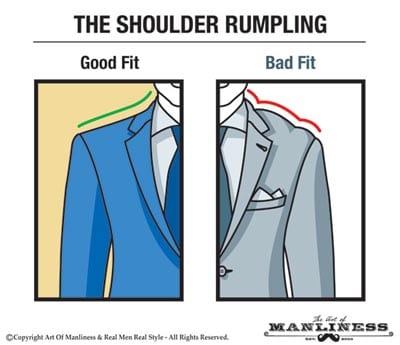

Shoulder Wrinkles — Top Rumpling

If you’re getting noticeable bunching on top of your shoulder, rather than on the upper sleeve, the jacket is too large in the shoulders.

This could be a simple length problem, but more likely it’s that the interior space is simply too large — your shoulders aren’t broad enough, front to back, to fill out the jacket.

Try a slimmer fit, if the manufacturer offers multiple styles, or a smaller size. If you’re still seeing wrinkles on the tops of your shoulders, the brand probably isn’t going to work for you.

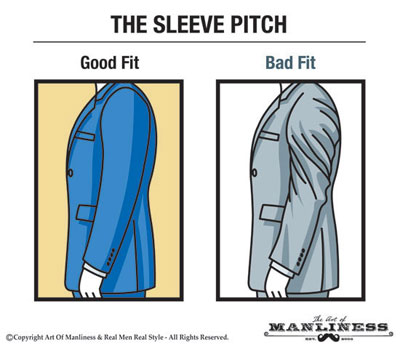

Twisted Sleeves — Bad Sleeve Pitch

Faint spiraling wrinkles on the outside of the sleeve occur when the angle of your arm in its natural stance doesn’t match the angle that the sleeve was constructed with. The result is a sleeve that looks slightly twisted even when your arms are hanging still at your sides.

A tailor can theoretically remove the sleeves and reattach them at a slightly different angle, but it’s not a simple or a cheap fix. Generally speaking, you can consider this one a deal-breaker. Keep trying until you find a jacket where the sleeves fall smooth and straight when your arms are resting in their natural stance.

Watch a Video Summary of This Post

_______________________________________

Written By:

Antonio Centeno

Founder of Real Men Real Style

Creator of The Style System – a college-level course that teaches the foundations of professional dressing so you control the message your image sends.